The Keweenaw Peninsula

October 22, 2015

En route, I had no thoughts of copper mines; I had forgotten that this was copper country. In any case I was going for the purpose of talking about chemistry. Sleeping on overnight flights is impossible, so I my thoughts were on the upcoming presentation, wondering if there was a purpose. What would chemists think of trajectories, intentions, and interventions? Did it matter? What had they thought of the title, “At the End of Chemistry”?

I sent them an abstract for posting the week before. Below the title the curious ones would read: “For more than a half century I have designed and created new molecules. My research has been shaped within the contexts of culture, time, and place, at times responding to the work of others, but always attempting to ride the wave front of science. “At the End of Chemistry” follows the trajectory of my research from rocket design in the 1950’s to nano-materials in the 21st century. It is both report and inquiry about the nature of research.”

The flight from O’Hare passed over Milwaukee, then Green Bay; as we flew north I followed the landscape below, watching Fall edge forward, from middle age to senescence. As we approached the Keweenaw Peninsula, in descent a translucent veil lifted, revealing Fall colors of curious intensity. Thirteen hours from liftoff in Portland, I was at my destination. It was 12:30pm. I was appreciative of the few hours sleep before the upcoming dinner with Fang and Marshall. Fang had been my student 11 years before; Marshall a friend from the distant past.

The schedule for Friday would be full of one-on-one visits, a grant workshop, and my seminar late in the afternoon. At the Library, one of the few craft breweries in the Houghton area, we discussed details of the visit, people and logistics. Fang had set aside Saturday to explore the upper Peninsula. This would be unusual for him. He almost always worked in the lab, or wrote papers and proposals on Saturday and Sunday. The Library was as much a museum as brewery. I found subsequently that most other places that I visited, no matter their business, had an aura of museum. Marshall summarized in one word. Copper. The Upper Peninsula had at one time been one of the great copper regions of the world. From 1842 through the mid 1900s more wealth was generated from copper here than in all the gold fields of California. Billions of pounds of copper had been extracted from the earth, a century ago the population swelled to over 100,000, but had dramatically dwindled as the copper became depleted.

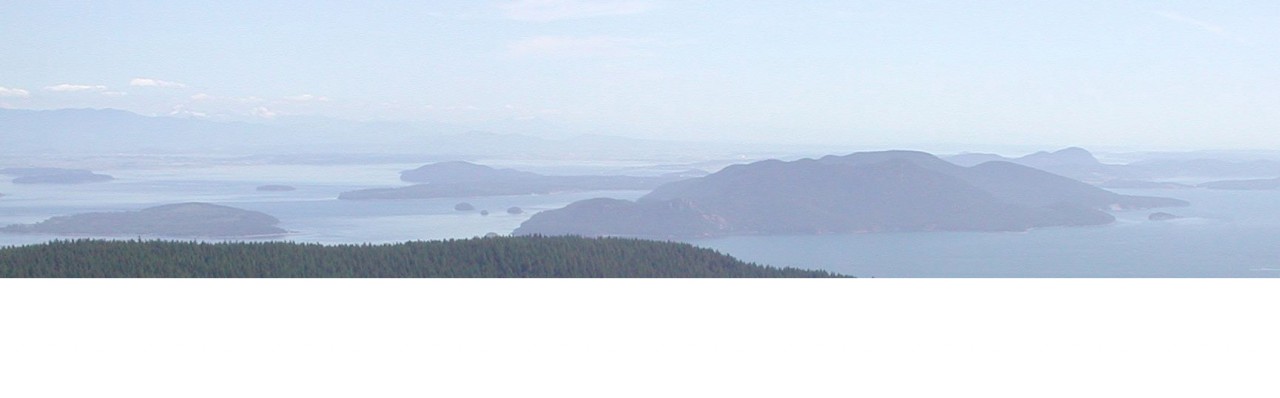

The Keweenaw Peninsula juts eastward into Lake Superior. Exposed to storms systems from the north, its winter’s are brutal. By mid-October, the shuttering of windows begins, and plans for trekking to southern regions gain urgency. I came as others were preparing to leave. Not that I would stay; four days I thought would be sufficient. It was not. It is impossible not to linger in ancient forests, on the tops of ridges with views extending for hundreds of miles, and in the stone ruins and rusted machinery of the American age of copper.

Marshall said, “you know you can go into the mines.” Into the mines?” I repeated, “into the copper mines”? I turned to Fang. “Have you been,” I asked. “No,” he replied. “You have been here ten years, and you have not been into the copper mines,” I stated incredulously. “No, I really did not want to,” he said. I stared at Fang. “We are going into the copper mines.” Fang knew that he would have to. Marshall said that there were guided tours at the Quincy mine, just a short distance north. “Guided tours?” I didn’t want a guided tour I wanted to descend on my own. The next day, Charlene, an administrative assistant found information on a more distant mine, which was open to visitors; there were no guides.

The schedule for Friday was tight, thirty-minute conversations with individual faculty; each talked about his/her goals, research achievements, and frustrations with funding and graduate students. The conversations were engaging, ideas and ambitions outmatching resources. A session on proposal writing later in the morning was attended by younger faculty. I focused on the meta-messages of reviewer’s critiques. This was the experience that they lacked, few had participated on review panels. I had instructed them to bring reviews of their proposals that we could dissect as a group. No one did. That was fine, I know what they say. I can recite their reviews without having ever seen them. Experience is s strange beast. At the end they said the session was very entertaining. Yes, experience provides you with the ammunition of lots of stories.

My presentation later in the afternoon started five minutes after three. Near the beginning I asked if anyone was familiar with the geneology of chemistry; the linage of who worked with whom down through the ages. None knew of this. Strange, to not be curious about your heritage. The records are deep, Fang worked with me at Purdue from 2000-2004, I worked with Hyp Dauben at the University of Washington, 1962-1965. The lineage continues mentor to student, through Bunsen at Heidelberg, Boerhaave at Leiden, da Thiene at Padua, William of Ockham at Oxford, St. Gilles at the University of Paris, back through the middle ages, through Odon de Cluny at the abbey of Cluny, further back through abbeys at Autun, to St. Irenaeus, to the Church of Asia Minor and the Apostle John Zebedee, and then after 84 generations to Jesus Christ. I move on, to a parallel lineage, through the guilds of medieval Europe then links to the workshops of Rome and ancient Greece. I talk about the connectivity of our craft, of purpose, method, material, and idea within the specificity of my own work. The talk passes by too quickly. Why was there so much to say; I think essential to me, not to them. I had covered a lot of ground, discussed half a dozen different projects, linked them to the broad networked world of science. Did anyone understand what had happened?

Sometimes we imagine that we are nodes in a network of ideas and people; yet most ideas become lost in the ether of space, never quite merging, at least not in the ways that we had intended. Most pass by the minds of others, not quite connecting; or when they pass through, they become lost among others more immediate and urgent. Now, as I write about the experiences of the trip, I think of Laura’s references to the spaces in between. I think of orthogonal networks; of the languages that define the networks, of the difficulty of translations between networks. There are entry points, but so few understand access. There is comfort in the security of the familiar. I think of Whitney’s rabbit holes; to which one have I retreated today?

On Saturday morning, Fang, his son, Marshall and I drive northeast, up the peninsula to the Delaware mine site. When we arrive no one is there; then a few minutes later, the owner appears, and we are given instructions and hard hats.

The descent is simple. We crouch to pass through a low opening. We descend on crude wood steps; light too dim to see where the stairway ended. We followed the light bulbs downward and within a few minutes arrived at level one. The eight levels below were inaccessible, permanently flooded, but level one extended northward for nearly 1/3 mile. In the absence of the shattering impact of steam drills, the experience was not exactly authentic, but still unique in the imposition of the dark. The owner said that they had aimed to recreate the dimness of the 1800s. Perhaps they had come close; bulbs were low wattage, widely spaced, and occasionally burnt out. We walked in silence, feet and path frequently invisible between lights. Is this how we always view the world? We walked slowly; there is no destination, only the journey. There are no markers; no signs; but as long as the lights remain on it is impossible to become lost. Side tunnels are blocked by stone and wood barriers.

Once outside we explore the grounds. The stone buildings in deterioration have become one with the landscape. So very peaceful; sad to leave, but we have miles of trails to explore further up the Peninsula.